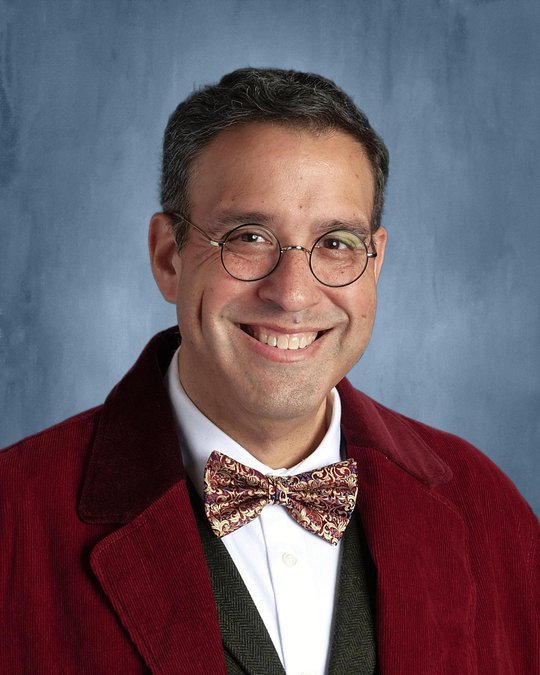

By DR. GEORGE MEGENNEY

Principal, Collegeville and Farmington

The topic of this article is a difficult one to tackle, but I firmly believe that it is necessary and important to do so with the intention of helping our community understand how Escalon elementary school staff deal with the problem of bullying. As the principal of our two smallest and outlying schools, Collegeville and Farmington, with a combined student population of just over 250 students, I can report that bullying is sometimes an unfortunate reality that students and staff have to confront, and also one that we work as a team to overcome. Addressing this problem and working to eliminate it when it is discovered is, however, more complex than most people realize.

When a student or parent informs the school about alleged bullying an investigation is triggered, and the first question that needs to be asked is whether or not a reported behavior is actually bullying. This begs the question: what is bullying? The answer may seem obvious, but due to the fact that the term ‘bullying’ is frequently misused, it ought to be defined for purposes of this article. The CDC defines bullying as, “...any unwanted aggressive behavior(s) by another youth or group of youths, who are not siblings or current dating partners, that involves an observed or perceived power imbalance, and is repeated multiple times or is highly likely to be repeated. Bullying may inflict harm or distress on the targeted youth including physical, psychological, social, or educational harm.” A poster I recently saw in a classroom may help us to frame bullying in a more straightforward manner and also help us to understand what it isn’t:

“When someone says or does something unintentionally hurtful and they do it once, that’s rude.”

“When someone says or does something intentionally hurtful and they do it once, that’s mean.”

“When someone says or does something intentionally hurtful and they keep doing it - even when you tell them to stop or show them that you’re upset - that’s bullying.”

Students accuse each other of bullying frequently. During recently held assemblies focused on the topic of school safety, a guest speaker took an informal poll of the student bodies at both Collegeville and Farmington. The question was a simple one: “How many of you have been bullied?” More than half of the students at each school raised their hands. This was both shocking and disappointing to see. Could it really be that more than half the students at each school had been or were being bullied? Or was this, as I am prone to suspect, a case of misuse and misunderstanding of the term ‘bullying’ to identify rude and mean behaviors that don’t meet the above definition?

I cannot speak to the experiences of my fellow elementary school principals in terms of their interactions with students, but over the course of the three-and-a-half years that I’ve been responsible for student discipline at Collegeville and Farmington, the number of actual cases of bullying that I’ve dealt with have been few. One aspect of school administration that most may not immediately recognize is that we have to wear the hat of an investigator from time to time. Whenever student-to-student conflicts arise, and when they are reported to school staff, investigating what took place and whether there was any wrongdoing becomes necessary. Our state’s education code requires all school administrators to treat all students fairly and provide them with the opportunity to explain their actions. In other words, the adage of ‘innocent until proven guilty’ should operate within schools when dealing with instances of students breaking school rules. In my experience, there have been many, many instances of ‘he said - he said, she said - she said, and he said - she said’ scenarios in which the only available evidence was the testimony of each student. Taking disciplinary action under such circumstances, beyond providing common sense advice and warning students about the consequences of misbehavior, is difficult.

One critical hurdle to overcome is whether or not a problem is ever reported. I have found that students often fail to report problems to their teacher, to instructional aides, yard duty, cafeteria staff, or the principal. Whether out of fear of being reprimanded, of not being believed, of retaliation from the student they accuse, of being labeled a ‘tattletail’ or ‘snitch,’ or other reasons, many students simply won’t report a problem. As I often remind students, we cannot help if we don’t know that something took place. Sometimes students report problems to their parents, which is helpful and a desirable behavior. After all, children should be honest with and maintain an open line of communication with their parents or guardians. However, reporting a problem to a parent while failing to report it to school staff delays the school’s ability to act on a problem and requires that the parent inform the school about the complaint. Once the problem has been reported, the mechanisms of investigation are triggered, most often resulting in interviews with students to sort out the details of what took place.

For those of you who are fans of mysteries, watching an investigator examine evidence and analyze witness accounts can be fascinating, and within the world of fiction, often satisfying once all the puzzle pieces are aligned together. Trying to sort out the words or actions of children, particularly when no adult directly witnessed an alleged event, very often results in stories that don’t align, and details that don’t match up. The challenge becomes all the greater when analyzing something that took place several days or weeks in the past because of a lack of immediate reporting. When and if an adult witnesses a student transgression, disciplinary action is most often straightforward and swift, however there are instances when events occur at a distance from supervising adults; such as during recess or on the bus. Typically it is during these unstructured times that student-to-student conflicts often take place.

Investigations of alleged bullying, particularly among students between kindergarten and third grade, most often reveal that reported behaviors fall within the first or second categories listed above: students being rude or students being mean. Unfortunately, that happens a lot. Younger students in particular have difficulty distinguishing between individual and isolated moments of rudeness or meanness and those that are repeated, consistent and specifically intended to target someone. When I interview a student who has made an accusation about bullying I ask the same questions: “Has this happened repeatedly? How often has it happened? Did anyone else see or hear it? Did you report it to any adult?” The answers to these questions determine the course of the investigation and follow up actions. If a student says it happened once (which happens a lot) then it is not bullying. If it happened on two or three occasions, separated by weeks or months, it is not bullying. This doesn’t mean that the investigation ends, or that follow up disciplinary action doesn’t happen. It usually does continue, and when and if it is found that a student has broken a school rule, appropriate consequences are imposed.

When actual bullying is determined to have taken place, remedying the situation is no less complex than rooting it out. I’ve come to discover that bullying comes in a variety of forms, including physical and verbal. Verbal bullying can also include online or electronic interactions also called ‘cyber-bullying,’ though that is more common as students get older and have more access to the electronic devices that serve as the conduit for this behavior. At the elementary level the bullying I’ve encountered has more often than not been of the verbal variety. Addressing it requires listening to and validating the feelings of the student who has been on the receiving end, informing staff about the problem so that they can be additionally vigilant and help to stop future problems before they arise, and perhaps most importantly as far as bringing the problem to a conclusion, helping the student who is doing the bullying to stop it.

I say ‘help’ because more often than not, the child who is bullying is behaving out of their own set of frustrations or anxieties and does not know how to direct or channel their feelings. Understanding the source of the behavior is the first step toward resolving it. This by no means justifies the poor choices a child can make with regard to how they interact with their peers, but it does allow us to paint a more detailed picture of the root causes. In my experience bullying behaviors have arisen from circumstances ranging from parents divorcing or with marital problems, a parent or family member who has been incarcerated, a death in the family, moving to a new school, just to name some of the more serious ones.

Bullying that is more subtle is much, much harder to eliminate. For example, students who want to be mean to someone they don’t get along with, perhaps even after conventional bullying has been discovered and addressed, show their dislike in ways that are rude, but which a classroom teacher or school administrator may have difficulty eliminating. This might include things like using facial expressions or body language to communicate distaste, being unwilling to work with or share in the classroom, behaviors that express exclusion and low opinion, but that aren’t outright violations of school rules. Combating this type of behavior requires cultivating a tool that will ultimately go on to help most students cope with the simple reality that not everyone will get along, be friendly or kind all of the time: developing resiliency.

Helping students to build a bit of grit is also challenging, but ultimately rewarding and has the long-term benefit of reducing the likelihood that they will be prone to feeling bullied when they are on the receiving end of a rude or unkind remark. I recently had a conversation with a student who reported that he was being bullied. When I asked the student the following question, “Do you value what he (the alleged bully) says?” he looked at me puzzled for a second and responded, “No.” “Then why should anything he says matter?” He told me thinking about it that way made him feel a lot better. For this particular student at that particular moment, he developed a bit more resilience than before our conversation. The result, at least since we had that talk, seems to have improved his particular circumstances. Every situation is different, as is the ability of each student to overcome the things that bother them.

In sum, I believe that if we work together as caring adults, including both school staff and parents, that our students can develop a uniform definition of what is and what isn’t bullying. We can help our students understand that by reporting problems to school staff that they can help bring about a faster resolution to problems. And, by developing a bit of grit, students can help themselves to overcome small interpersonal conflicts and focus on the things that really matter when developing their social skills: building self-confidence and self-worth.

Principally Speaking is a monthly article, contributed by principals from Escalon Unified School District sites, throughout the school year. It is designed to update the community on school events and activities.